|

| Bing prompt: "Draw a businessman leaving China". |

Hot on the heels of the previous post about how Chinese are showing at the United States' southern border seeking asylum from increasingly dire economic conditions in the PRC, we get more news of this sort. Just as people are leaving China, so is capital: For the first time its records, the PRC has seen a net outflow of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). On balance, more FDI is leaving than entering China, once the world's most notable destination for investment. From the Nikkei Asia Review:

Outflows of foreign direct investment in China have exceeded inflows for the first time as tensions with the U.S. over semiconductor technology and concerns about increased anti-spying activity heighten risks. The shift was reflected in balance-of-payments data for the July-September quarter released Friday by the State Administration of Foreign Exchange.

FDI came to minus $11.8 billion, with more withdrawals and downsizing than new investments for factory construction and other purposes. This marked the first negative figure in data going back to 1998.

To be sure, there are overseas precursors for this shift. The US is keen on banning cutting-edge knowledge on semiconductors and artificial intelligence from leaking to China:

Escalating tensions with the U.S. are one reason for the decline in foreign investment. In a survey taken last fall by the American Chamber of Commerce in the People's Republic of China, 66% of member respondents cited rising bilateral tensions as a business challenge in China.

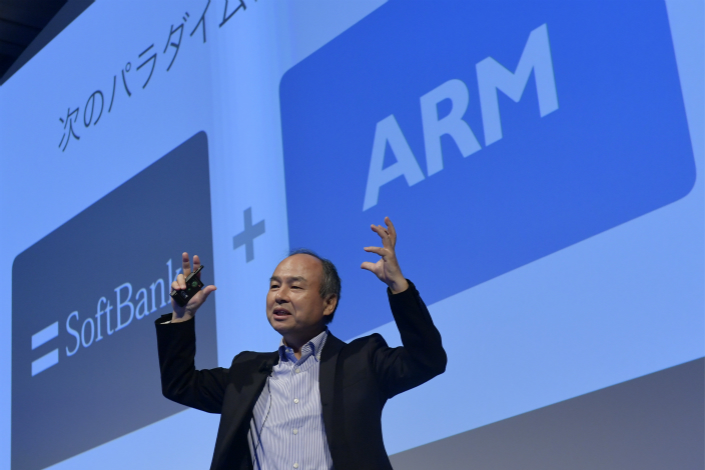

In August, the U.S. announced tighter restrictions on chip and artificial intelligence investment in China. Washington is coordinating with Beijing ahead of a summit meeting between Presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping in November, but the U.S. remains committed to technology restrictions in the name of economic security.

Looking at foreign investment in the semiconductor field by destination, China's share has already shrunk from 48% in 2018 to 1% in 2022, according to U.S. research firm Rhodium Group. In contrast, the U.S. share rose from zero to 37%. The combined share of India, Singapore and Malaysia grew from 10% to 38%.

However, American chip and AI concerns obviously do not make up all potential sources of FDI to China. It is here where a decidedly unfriendly foreign investment policy climate factors in. You name it: from corporate espionage to various forms of harassment of overseas businesses under dubious pretenses... today's PRC leadership does not think much of how others perceive these actions meant to promote domestic industry at the expense of foreign concerns.

Europeans, for instance, cite only cosmetic efforts to improve prospects for FDI:

Beijing has been seeking to reverse capital outflows in the face of mounting economic challenges. But such efforts appear to have failed to assure investors. The China International Import Expo (CIIE), an annual event launched by President Xi Jinping in 2018 to portray China as an open market and improve its trade ties, kicked off on Sunday. But the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China criticized the event last week as a “showcase.”

“European businesses are becoming disillusioned as symbolic gestures take the place of tangible results needed to restore business confidence,” the chamber said in a Friday statement. “The CIIE was originally intended as a showcase of China’s opening up and reform agenda, but it has proven to be largely smoke and mirrors so far,” Carlo D’Andrea, vice president of the chamber, said in the statement.

Having done nearly everything possible to discourage FDI, is it any wonder it's leaving China?