Not so long ago business students flocked to Europe. Compared with their American counterparts, European schools were cheaper and their student bodies more diverse, both attractive features—and the salaries of European MBA graduates were often higher, too. Some of these attractions remain undimmed. But they are no longer enough to bring in the punters. Data from The Economist’s latest ranking of full-time MBA programmes (see article) suggest the appeal of an Old World business education has gone into a rapid decline.The lack of opportunities for post-study work are also hurting enrollments alongside tightening of visa rules. Besides, are there even jobs to be found in the UK which has had three straight quarterly declines in GDP?

One obvious reason why students might stay away is the dire economy. MBAs can look like a good way to sit out a short downturn. In a longer one they lose their charm. With no job-producing European recovery in sight, going there for an MBA seems not so much cleverly counter-cyclical as stubbornly contrarian.Where to go then? Aside from tighter visa rules for foreign students, the UK and US share scant job prospects and declining wages besides. It's up to the more progressive lands of Australia and Canada to pick up the slack, then. While those nations also have their fair share of xenophobes, the general sentiment toward foreigners and the economic outlook is brighter in these lands:

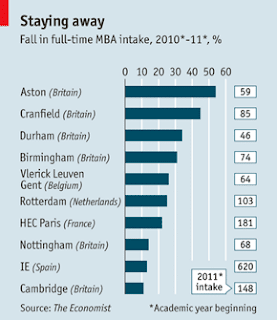

Europe’s slide also reflects a problem specific to its most important MBA market. The average class size of the British MBA programmes ranked by The Economist has decreased by 11% over the past year. Schools blame Britain’s newly toughened visa requirements for non-EU students. Graduates used to have an automatic right to stay and work for two years. Now, they must find a sponsoring company and land a job which pays at least £20,000 ($32,000) a year. The number of visas available to students wanting to start their own business is piddling.

The fact that European schools are struggling is particularly galling because America has also made it more difficult for foreign students to work in the country after graduation, providing what should be an extra opportunity for the Europeans. American MBA programmes are typically twice the length of those in Europe, making both the cost and the opportunity cost of studying there higher. The salaries earned by American MBA graduates have been stagnant for over a decade. All this should have spurred students from poorer countries to apply to European schools.As before, I think that the university system in the US and UK are the canaries in the coal mine for higher education in these countries. Locals graduates cannot find jobs--nor can foreign students it seems who you would think have more opportunities elsewhere. What then is the rationale for universities that prepare local and international students for non-existent jobs?

Instead, the countries doing well out of America’s closing doors and high costs are Canada and Australia. Australia recently ditched its own strict policy on student visas in favour of a more welcoming approach. And Canada has perhaps gone further than any country in wooing overseas students. As of 2008, all students who have completed a two-year master’s degree automatically have the right to stay in the country and work for three years. They do not need to have a job lined up and are not restricted to working in a field linked to their studies, as they would be in America.

While you may not get the impression reading different blogs from others in academia (professorial rent seekers ey?), make no mistake that higher education is broken in these countries and needs much fixing to stay relevant. Alas, I believe that the gales of creative destruction will remake higher education as we know it--especially if it continues to be increasingly irrelevant to the fundamental task of improving employment prospects.