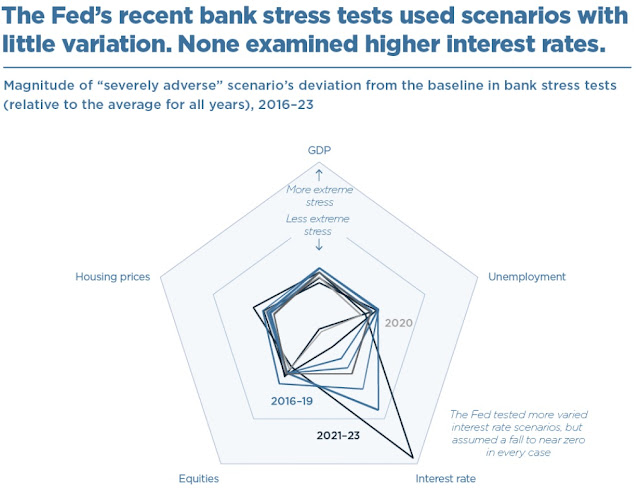

Comparatively speaking, stress tests conducted Stateside may not be sufficiently rigorous in simulating scenarios that are detrimental to financial sustainability. It is fairly obvious that the higher rates we have these days are causing mismatches between what banks earn and what they must pay out. Oddly, however, recent US stress tests have not involved rising but rather falling interest rates. See the illustration above and commentary from the Peterson Institute:

But it’s not only for 2023 that this feature appears. Indeed, every severely adverse scenario used by the Fed since 2015 has the 3-month Treasury bill rate ending up at 0.1 percent. Many historic episodes of severe economic downturn have indeed been accompanied by low interest rates, as the Fed used its policy tools to support aggregate demand. But it is a bit strange that not since 2015 has a stress test involved rising interest rates.

One of the advantages of stress testing the banks every year is that their robustness to a variety of contrasting stresses can be assessed. Just repeating a broadly similar scenario year after year misses the opportunity to provide supervisors with potentially important information on vulnerabilities. It can also result in policymakers assuming that the banks are robust to more types of shock than is really the case.

Yet pointlessly repeating a broadly similar scenario each year is exactly what the Fed has been doing, as we can show here.

Have other regulatory authorities been administering stress tests as lax and unrealistic as American ones? Thankfully for the rest of the world, the answer is no. The European Central Bank--and remember that Switzerland is not an ECB member for those thinking of a certain defunct bank--has done its homework by simulating interest rate rises just as we are experiencing now:

Overall, our [ECB] analysis shows that the euro area banking sector would remain broadly resilient to a variety of interest rate shocks. That would hold also under a baseline scenario of an economic slowdown in 2023 with the risk of a shallow recession, such as the scenario included in the December 2022 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections. Profitability would increase overall, driven by [higher] net interest income. However, provisions would also increase, reflecting potential difficulties for borrowers. Results for the overall impact on solvency remain on average fairly muted with great heterogeneity across banks, within and across different business models

The same hold true for Australian banks. Down under, their stress tests have likewise gamed out the implications of higher interest rates:

Higher inflation and higher interest rates could lead to larger credit losses despite continued, albeit slower, economic growth. The stress testing model can provide insights into the magnitude of potential credit losses and how important they could be for the capital positions of large and mid-sized banks. The model applies two principal stresses to examine the resilience of the banking system to higher inflation and interest rates:

- Higher inflation and higher interest rates on mortgages squeeze households’ real incomes, making it more difficult to service debt, which could lead to more defaults and larger credit losses for banks. Similarly, higher input costs and higher interest rates passed onto business loans can make it more difficult for businesses to service their debts, potentially leading to higher default rates (see ‘Chapter 2: Household and Business Finances in Australia’).

- Higher interest rates typically reduce the prices of housing and commercial property that are held as collateral by banks against their loans, which increases LGDs as well as PDs on loans.

Having conducted these sorts of tests well before 2023, Australian banks look to be on firming footing.

While we hope that contagion does not spread to the Eurozone and the land down under, it certainly bears questioning why US stress tests did not involve scenarios involving deteriorating financial conditions due to sustained central bank rate rises in the face of persistently elevated inflation. While the subject matter can come across as esoteric, such things do impact Joe Average since taxpayers will ultimately foot the bill for cleaning up the mess caused by unstressful stress tests giving false comfort to financial authorities about the soundness of banks they regulate.

UPDATE 1: Also see Krishna Guha's commentary in the FT. He warns that while the ECB did conduct asset side stress tests (e.g., holding low-yielding securities), it did not test how vulnerable Eurozone banks were to depositor flight like what has happened Stateside. That said, European depositors tend not to move their money around.

UPDATE 2: Former Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation chief Sheila Bair says the same thing about the latest batch of stress tests that banks passed: They did not model rising interest rates.