|

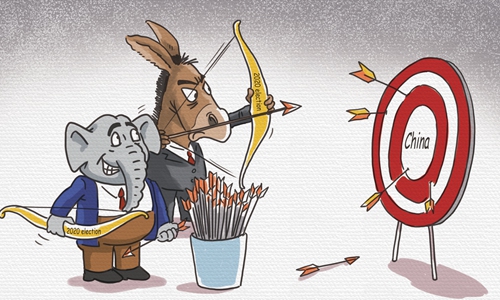

| At least Chinese state media's take on the topic is obvious. |

Puns on the term "offshoring"--moving one's production facilities abroad, or having foreign-based concerns manufacture components for you--have proliferated. Some time thereafter came the term "reshoring" to denote moving back production to where something was once manufactured. (A US firm moving its plant back to America from China would be the most obvious example.)

Now we have the slightly more convoluted term "friendshoring" care of Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. Like reshoring, friendshoring concerns moving production to locales more favorable to the company in question. For instance, if you had a plant in China, you may be moving it to Mexico to avoid Communist Party persecution of foreign firms through discriminatory regulation. Hence, both reshoring and friendshoring concern moving business activities to where authorities are more favorably disposed. However, the difference is that while reshoring is moving production back to where something was once made, friendshoring does not presume moving back, and the destination can be anyplace where authorities are amicable. That is, your risk of being put out of business by some Western-hating foreign autocrat is mitigated.

Or is it? There are a number of viewpoints out there regarding whether friendshoring is actually beneficial. The consulting firm Korn Ferry cautions that this practice may instead create enemies among countries you have chosen to leave. It boils down to the extent to which companies want to involve themselves in international politics:

“Friend-shoring can be extremely risky,” says Tom Wrobleski, co-leader of Korn Ferry's Supply Chain Talent Optimization practice. “You’re picking sides and can unintentionally forge bad blood with other countries.” In the long term, this could backfire if the country your company relies on—for lithium for batteries, say, or precious metals for computer chips—feels alienated...

The puzzle grows still more complicated when it’s infused with values and politics, says Wrobleski, who says these considerations play an important role in the decision-making process. “There must be balance between political alignment and the actual reason for doing business in a particular country,” says Wrobleski.

Speaking of politics, the Wall Street Journal adds that the wider effect of firms choosing sides by classifying the world into friends and foes through their location decisions could result in the fragmentation of global supply chains. "Unfriendly" countries may feel antagonized and choose to keep to themselves more. In so doing, key commodities and burgeoning markets that were previously open for business may become increasingly unavailable. This situation may partly explain the higher inflation being experienced worldwide nowadays. In economic jargon, diminished global economic integration increases trade frictions and therefore the ease and cost of doing business worldwide.

Weighing matters, Raghuram Rajan urges us to "just say no" to friendshoring. Insofar as many poor countries are led by authoritarian figures who may come across as business unfriendly to Western firms, development may be hampered:

The benefits [of trade between rich and poor countries] are obvious. Final products are significantly less expensive, so even the poorest people in rich countries can buy them. At the same time, developing countries participate in the production process, using their most valuable resource: Low-cost labour. As their workers gain skills, their own manufacturers move to more sophisticated production processes, climbing the value chain. As workers’ incomes rise, they buy more rich-country products...

If any forthcoming friend-shoring mandates were to apply such a broad categorisation, they would have devastating effects on international trade. After all, friend-shoring will typically mean trading with countries that have similar values and institutions; and that, in practice, will mean transacting only with countries at similar levels of development...

The benefits of a global supply chain stem precisely from the fact that it involves countries with very different income levels, allowing each to bring its comparative advantage to the production process, PhD researchers from one, for example, and unskilled assembly-line workers from another. Friend-shoring would tend to eliminate this dynamic, thereby increasing production costs and consumer prices. While some labor unions would welcome the reduced competition, the rest of us would regret it.

On top of diminished trade benefits, Rajan reiterates that friendshoring may encourage protectionism among those being discriminated against. What is a global supply chain manager to do? I'll have more to say about this topic in the future, but for now, it's safe to say that each company will need to weight the benefits of more predictable supply chains with likely costlier production in friendlier locations and the potential loss of market access to aggrieved "unfriendly" countries.

PS: If you have doubt the admittedly unwieldy term "friendshoring" is real, the IMF is already observing greater FDI among geopolitically aligned countries. The IMF further estimates potentially large efficiency losses due to this phenomenon.